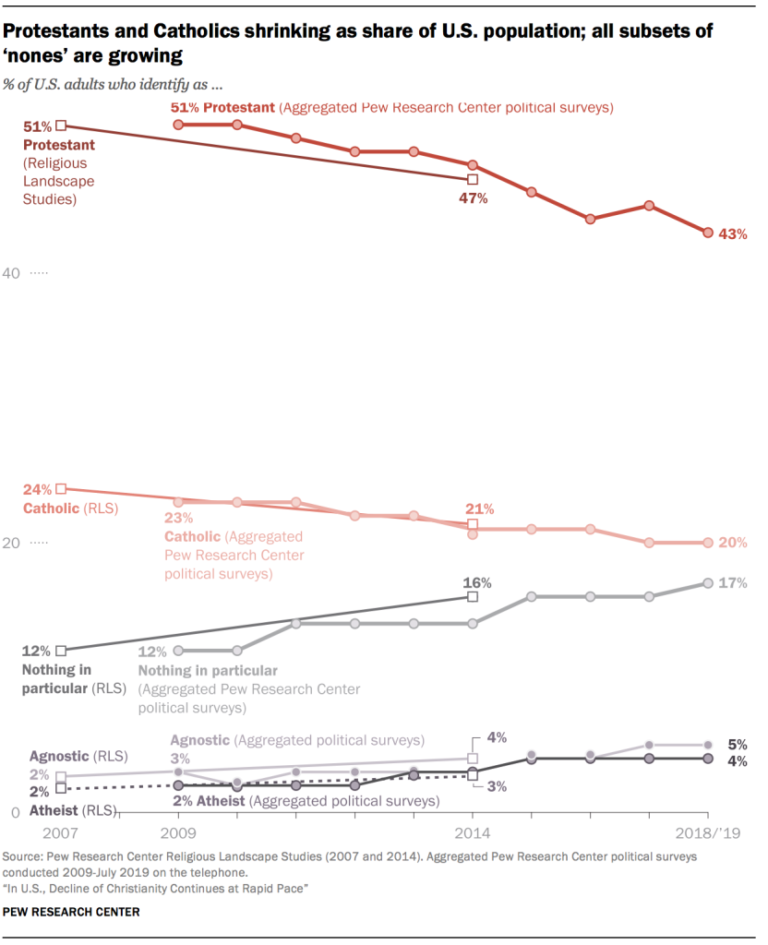

The Pew Research Center recently published an alarming report: “In U.S., Decline of Christianity Continues at Rapid Pace.” Since 2009, the religiously unaffiliated have risen from 17% of the population to 26% in 2018/19. And today only 65% of Americans identify as Christians, down from 77% only a decade ago.

The report points out that there’s a generational dynamic at work as well. A full 8 in 10 members of the Silent Generation are Christians, as are three-fourths of baby boomers. Yet today, less than half of Millennials call themselves Christians, and 40% are religious “nones.” That is, when asked about their religious affiliation, they respond “nothing in particular.” There are now 30 million more “nones” in America than there were just a decade ago.

Sobering stuff. Whether it’s church attendance or looking at the religious preferences of Whites, Blacks or Hispanics, the decline of Christian belief in the past generation of Americans seems to be picking up steam.

Some push back on this thesis: Glenn Stanton, a conservative researcher at Focus on the Family, claims that news headlines about the “dying church” are overblown. He accurately points out that the greatest numerical declines are in mainline churches, and that the numbers of evangelical Christians are holding strong. Indeed, even Pew reports that though the overall number of Protestants among U.S. adults has declined from 51% in 2009 to 43%% in 2019, the number of evangelical Protestants has grown in the last decade from 56% to 59%.

Stanton and others point out what is happening: that the “middle is falling out.” Those who used to be nominally Christian now feel no need to say they’re a Christian of any sort when a pollster asks. Many of these people get lopped into the “nones” category but are not necessarily atheist or agnostic. “Nones” is a complex category of those without strong ties to a denomination or faith tradition.

Historically, American exceptionalism held true in religion. As other rich countries secularized rapidly, especially in Europe, America didn’t follow suit. But since 1990, we now have about 30 years of data that shows belief is indeed falling.

What sense should we make of this data?

Though I wouldn’t use the word “crisis” (the internet doesn’t need one more alarmist article), I would like to lay out three problems that confessing Christians need to pay attention to as belief recedes in America.

(1) The politicization of faith is reshaping how Christians express their faith in public and how they’re perceived by the broader culture.

As I read over these Pew research findings, I ask “How would many of the Christian young adults in Denver respond to the question: ‘Are you a born-again evangelical?’”

My guess is that many wouldn’t reply “evangelical” because the word now has political and fundamentalist connotations. Though we work with many who would consider themselves theologically conservative, they’re also culturally-engaged, justice-minded, and have found themselves exiled from either the political right or left. As pastor Tim Keller eloquently said for many, historic Christianity doesn’t fit into a two-party system.

Derek Thompson, senior writer for The Atlantic, makes a convincing case that a few historical factors led to America losing its faith. One was that the Moral Majority, led by figures such as James Dobson, Jerry Falwell, and Pat Robertson, aligned Christian belief with Republic politics. Another factor was that, after 9/11, all religion got looped together with extremism. Either way, there are millions that now hold orthodox Christian belief but don’t align with either the right or the left.

I see this every day at Denver Institute. As a matter of fact, my guess is that one of the main drivers of event attendance is that there’s a growing number of Christians (and, I’d argue, a good number of the “spiritual but not religious”) who want to distance themselves from political narratives about faith, but desperately want to find their “tribe.” They want to find others who care about faith and our culture, yet don’t find those communities either in their churches or their places of work. They’re simply looking for like-minded friends.

As old alliances fade away, a growing number of philanthropists, investors, business leaders, and other professionals are embracing vocation as a way of being public about faith without being political. Teaching students, attending to patients, serving clients, and fielding customer calls can be every bit as much a public act of faith as voting.

Indeed, daily work is becoming central to a growing number of Christians who are committed to living out the Lord’s prayer “May your kingdom come, may your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven,” but who are uncomfortable with the categories placed on them by a shifting culture.

(2) The retreat from culture sounds appealing, but it isn’t a real option.

In the past several years, some have suggested that attempts to “renew culture” should be abandoned completely and that we should prepare for a new “dark ages” in which Christian communities can only preserve the knowledge of the truth – like medieval monastic communities – as culture careens into an abyss.

Yet my conviction is that a retreat from culture undersells how deeply connected we are in the modern economy, and that for every meal we eat, for every message we send, for every mile we drive, we need each other.

We can’t fully retreat from culture. The reality is that culture is the air we breathe.

The world we live in influences our emotions, our thoughts, and our dreams. And by not talking about these realities in our faith communities (or by simply turning up the worship music and smoke machines), we unthinkingly adopt the norms of the world around us.

Which leads me to my last point….

(3) The accommodation to a secular culture poses a real problem for Christians.

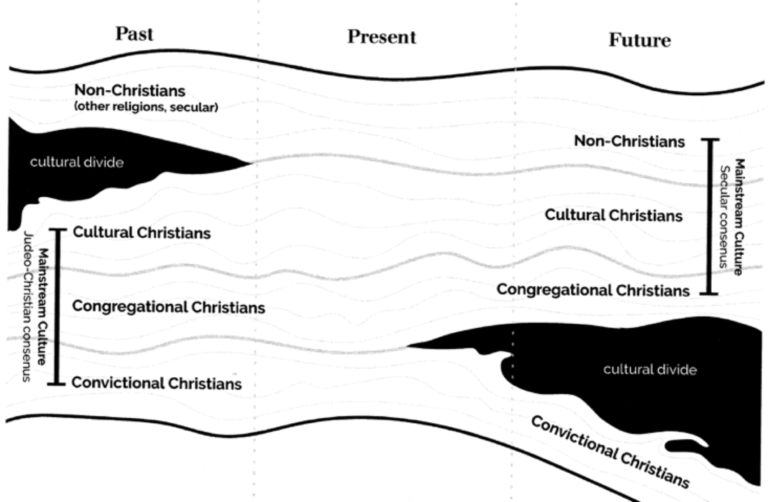

Why is it that social media and news if filled with such vitriol, including many who profess Christian belief? Ed Stetzer, a missiologist at Wheaton College, has helped to sort this one out for me in a single image.

The short of it: Fifty years ago, the broad cultural consensus on social issues had a Judeo-Christian consensus. This included “convictional Christians” (those who really believe all the doctrines of historic Christianity) as well as congregational Christians (occasional church attenders) and cultural Christians (those who don’t attend church but call themselves Christians because of family or tradition.)

Today, that consensus has drastically shifted. Today, the broad cultural consensus is secular on most social issues, and those who hold traditional views feel backed into a shrinking corner. Hence, you get many self-professed evangelicals who seem to be among the most combative voices out there, hoping to recover a nostalgic vision of American Christian that supposedly peaked in post-World War II America.

Here’s what I think: There are many Christians who are searching for a way to be hopeful yet not combative; who want to be faithful to countercultural Jesus yet engaged with the world around them; who are among the many “Christians who drink beer” and are tired of the culture wars, yet are deeply concerned about the world we live in.

Yet, in my view, there are very, very few models for this kind of life. If I work for a Fortune 500 company, what practices should I embrace, and which should I abstain from? What does faith look like in the immensity of modern health care? When has my faith become individualistic and consumeristic? How should I practice my faith in my family, community, or workplace? When have I accommodated to mainstream secular culture, and what on earth does it mean to be “distinctly Christian” in a pluralistic society? How shall Christians remain “activated” as followers of Christ during the week?

In our post-Christian culture, we are no longer Nehemiah, trying to rebuild the walls around a once-great Jerusalem. We are now Daniel, looking for ways to be faithful to God in Babylon.

Doing this requires hard thinking, faithful imagination, and robust communities of practice – communities that we’ve only just begun to build.

Jeff Haanen is a writer and entrepreneur. He founded Denver Institute for Faith & Work, a community of conveners, teachers and learners offering experiences and educational resources on the gospel, work, and community renewal. He is the author of An Uncommon Guide to Retirement: Finding God’s Purpose for the Next Season of Life and an upcoming two-book series on spiritual formation, vocation, and the working class for Intervarsity Press. He lives with his wife and four daughters in Denver and attends Wellspring Church in Englewood, Colorado.